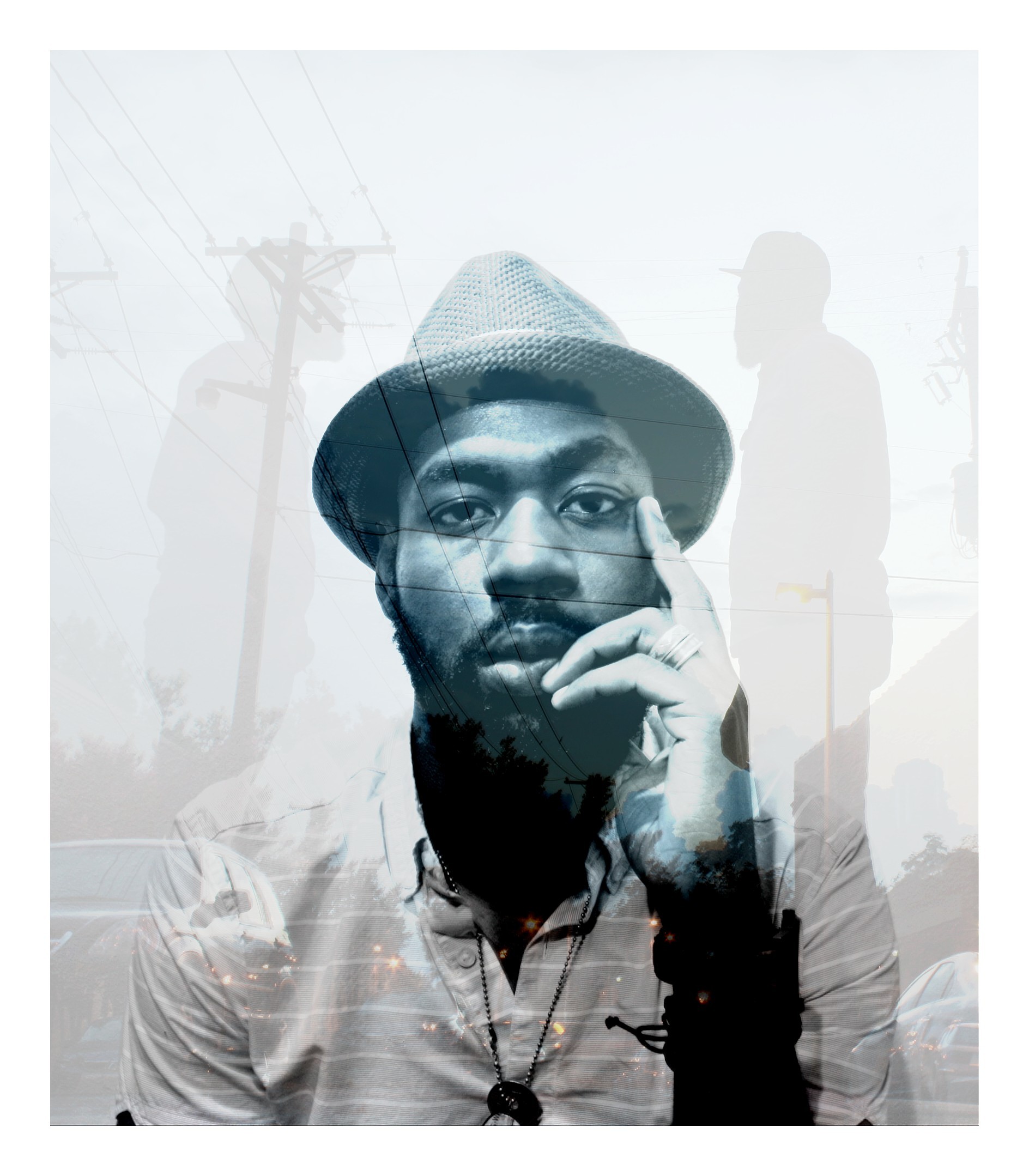

The Man Who Won’t Sit Still: The Photography of Joshua Asante

WORDS / ANDREW MCCLAIN

PHOTOS / JOSHUA ASANTE

Joshua Asante wants dialogue. Journalists will note that this is a rare trait among musicians, and as a member of Little Rock bands Amasa Hines and Velvet Kente, Asante has become a staple of the central Arkansas music scene. Musicians can often be quick to shrug off discussion of their music in favor of letting it speak for itself, but as Asante prepares for an exhibition of his photography at Hearne Fine Art, he’s eager to discuss the implications of his photographic work.

“I always have at least two or three cameras with me,” Asante says. As someone who never went to school for photography, he values the content of his work over the technical qualities that professional photographers prize. “The best camera is the one that you have in your hand,” he says, quoting a mentor of his.

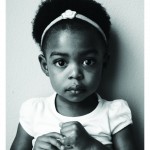

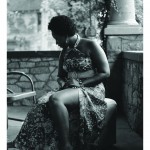

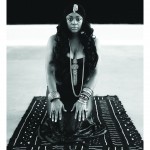

Asante wanted to present a narrative through his photography, so the exhibit, entitled “Eve Everlasting: Extended Maternity in the African Diaspora” has a very specific focus.

“The idea for the project came from a conversation with a friend of mine,” he says. “She said that when she got married, her husband’s mom made a statement saying that she had raised her son up to this point, and now it was the wife’s turn to take over. She was like ‘bullsh-t! I don’t wanna raise a dude!’ And a few years into the relationship, she realized what [her mother-in-law] meant. She didn’t necessarily mean ‘bring him into maturity,’ she meant that those things that are innately maternal – ‘you’ll be doing that more than I will now’ – All the positive aspects of your personality are going to help cultivate his life.”

This account, coupled with Asante’s observations on relationships, piqued an interest in what he calls “the woman’s perception of self; how she evolves, how that relates to how she mothers her own children, the men that she encounters in her adult life” as a subject for photography.

“There’s a very symbiotic thing that goes on, and a lot of it is an extension of maternity,” Asante says, “And not necessarily in the sense that, as men, we have a need to be coddled the way our mothers would. Even if you’re a guy who doesn’t date women, you still have this maternal aspect of the women that are close to you that extends beyond what your mother could do for you.”

So with the themes of womanhood and maternity in mind, Asante chose a spot in a friend’s house, a bedroom mirror adjacent to a bathroom, as the spot where he would photograph a number of women. Asante had never attempted a project of this scale before, and saw it as an exercise in repetition, since he wanted about 25 images for the series, and approached 43 women to be photographed. He got exactly 25 responses, and photographed all of them over the course of one weekend, using only natural light, regardless of the time of day.

“I photographed all the women into this mirror, to where they would be outside of this room, and I’d take their photograph in the mirror. They couldn’t see themselves, but they could see me. That’s a lot of what parenting is about,” Asante says. “It’s about kids – blinders on – it’s about the kids. A lot of times, parents are doing things that are detrimental to themselves and detrimental to the kids, because they can’t see themselves.”

Asante shot the entire series on a digital camera and put the prints on watercolor paper, which gives the photos a specific textural quality that he prizes. He very quickly realized the difficult implications of this project’s subject matter.

“I have a old friend who is a professor at San Diego State, and I approached her about doing it, and she was super reluctant,” Asante says. “She made a lot of good points. She’s a writer, and she felt that I was basically using the women without their consent as vocabulary for my narrative… and I can see that.”

But Asante welcomes dialogue around his narrative of womanhood. On this point, Asante holds fast: “What I’m saying is, this is an absolute truth: whether or not you want to be mothered, you will be; whether or not you want to have maternal aspects to your personality, you will have them, and this is just an examination of things that I feel like are true. Now, will that truth have room to evolve? Will it mean something else to you than it does to me? Yes. But, at its core, it exists.”

One reason Asante was eager to have this exhibition at Hearne, a gallery that deals primarily in African-American art, was their practice of doing panel discussions on the art that they show, and he wants his friend, the professor, to come participate in the discussion when the show opens. The photographs may very well ask more questions than they answer, and to that end, Asante will get what he wants: dialogue.

The “Eve Everlasting” opens at Hearne Fine Art in Little Rock in August, running through September.

Comments