JUST SHORT OF ESCAPE VELOCITY: Reflecting on the life of Charles Portis

WORDS / JAY JENNINGS

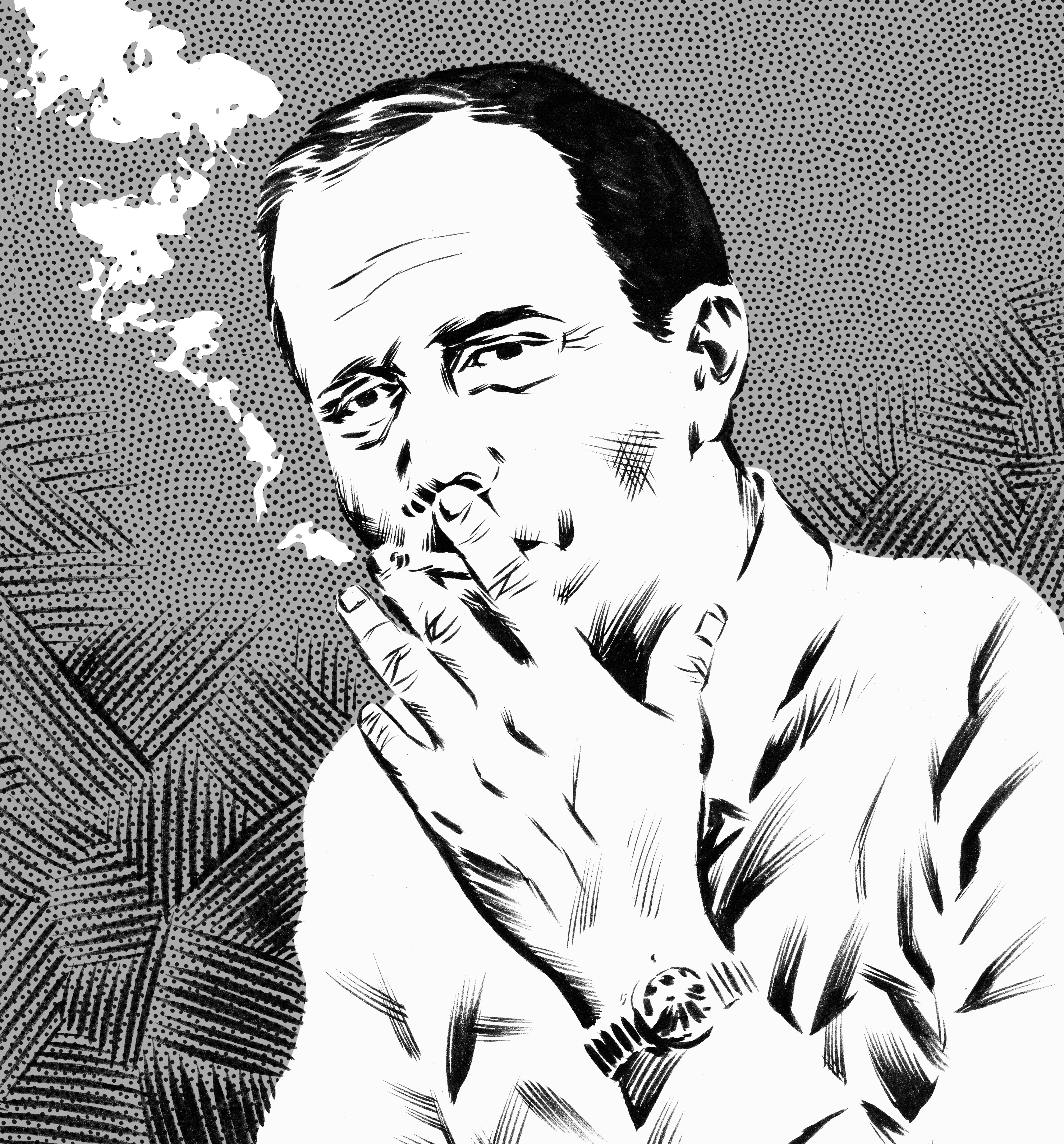

ILLUSTRATION / CHAD MAUPIN

Very few Arkansans go away and stay away. Sam Walton stuck around even as his retail operation spanned the globe. Bill Clinton plunked his presidential library back in the state. Stephens Inc. goes toe-to-toe with Wall Street firms but doesn’t feel compelled to stray from Center Street in Little Rock. Charles Portis fits the mold of the Arkansan who roamed and then returned (though he doesn’t fit any other mold), and as usual he acutely observed and wryly articulated the phenomenon, through the voice of Ray Midge in the novel The Dog of the South: “A lot of people leave Arkansas and most of them come back sooner or later. They can’t quite achieve escape velocity.”

Those last two words gave me the title for the collection of Portis’s work I edited, subtitled “A Charles Portis Miscellany.” Arkansas runs through the book, like the state’s namesake river, but Portis’s Arkansas is not one of sweeping pronouncements and grand flowing waters, but sideways glances and trickling creeks. (Portis would never have called any work Arkansas, as did the poet John Gould Fletcher for his striving epic; now that I think about it, Fletcher couldn’t achieve escape velocity either.)

In the one extended autobiographical piece Portis has published, “Combinations of Jacksons,” he recounts a childhood of margins and borders: he hears tales from his great grandfather about service on the Western edge of the Civil War, so unlike the carnage of Gettysburg, a thousand miles away; he recalls his own attempts, at age eight, to escape capture by imaginary Nazis (who of course weren’t pursuing anybody in Arkansas) by hollowing out a reed and submerging himself in the creeks around his home in Mount Holly, “in Union County, Arkansas, which adjoins Union Parish, Louisiana.” Though Arkansas is landlocked, hours from any coast, what place is more marginal than one people aren’t paying any attention to?

When Portis decided to try a career as a novelist, after distinguishing himself with a journalism career that took him to its peak – the London bureau chief for the New York Herald Tribune – he returned to a cabin on the White River and wrote Norwood. Tom Wolfe, the novelist and a onetime colleague at the Herald Tribune, has famously exclaimed about the location of his labors, “A fishing shack! In Arkansas!” Later, Portis moved to Little Rock and would launch himself from there to places even farther afield, both geographically and imaginatively: McAlester, Oklahoma; dusty towns in Mexico and British Honduras; a number of odd lots in Texas like La Coma; and Burnette, Indiana, “the most fashionable suburb of Gary.” While his peers like Wolfe, John Updike and Philip Roth were plumbing the depths of suburban and urban malaise, Portis was roaming the forgotten places and finding American dreamers and schemers.

For all that he has lived 70 or so years in Arkansas, the state is not a fundamental part of the fictional world of his novels. Norwood Pratt lives in east Texas and merely passes through Arkansas—slamming on the brakes once, disastrously, to watch a possum climb through a fence—on his way to New York and back. Mattie Ross of True Grit is proudly from Yell County but lights out for the territory on her revenge quest before coming home to spend her spinsterhood and eventually tell her tale. Ray Midge of The Dog of the South departs and returns to Little Rock but mostly wanders through Texas and into Mexico in search of his wife and Ford Torino. And the word “Arkansas” makes

a lone appearance each in Masters of Atlantis (“Moaler was in his Arkansas duck blind”) and Gringos, where Jimmy Burns IDs himself as being from the Arklatex, and even then from Louisiana.

If Arkansas has a claim on him, it is as the place where he learned to listen. In an interview with his former Arkansas Gazette colleague Roy Reed, Portis notes that his father’s side of the family “were talkers rather than readers or writers. A lot of cigar smoke and laughing when my father and his brothers got together. Long anecdotes. The spoken word.” Portis’s “ear” was honed in Arkansas while reading too. He worked for the Northwest Arkansas Times when he was a journalism student at the University of Arkansas and edited dispatches from “lady stringers in Goshen and Elkins,” he tells Reed, and his job “was to edit out all the life and charm from these homely reports. Some fine old country expression, or a nice turn of phrase—out they went.”

Portis took his Arkansas ear and traveled and listened to people at the margins, whether they were characters like Cezar Golescu from the Caspian Sea or Mattie Ross from near Dardanelle in Yell County. He heard them and conveyed this truth back to us: America is almost all margin.

1 comment

When’s his next novel coming out?