THE EMPATHY MACHINE

THE EMPATHY MACHINE: How Virtual Reality allowed filmmakers Ayana Baraka and Spade Robinson to tell the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre

WORDS / CASSIDY McCANTS

During her time at the University of Southern California’s Mixed Reality Studio, Ayana Baraka learned that viewers experience virtual reality like a memory. A longtime lover of storytelling and history, she found VR to be perfect for teaching—particularly for historical narrative.

Baraka was inspired by artists like Nonny de la Peña, “the godmother of VR,” and made several connections in the industry while at USC. She also had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Olivia J. Hooker, who was, at that time, one of the last known survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. Baraka got to sit with her and hear her story just a few years ahead of the massacre’s centennial, and she couldn’t believe no one else was getting her story.

Immediately, Baraka wanted folks to meet Dr. Hooker, to experience what she was experiencing during her chats with this woman who, at 102 years old, was still passionate about sharing the history of the massacre in Tulsa. According to Baraka, she wanted to help “connect the dots for Black communities today. With the story of North Tulsa, the majority of people I talk to say it’s a microcosm of the greater US.”

Naturally, Baraka was inspired to tell the story with VR. She teamed up with her writer-director friend Spade Robinson, who she’d worked with at USC and the Sundance Film Festival. It took them three years to get funding, and much of this time was spent working to overcome the fact that not many people knew about either the massacre or VR. “I wanted people to be able to sit across from Dr. Hooker and look into her eyes,” Baraka said.

Unfortunately, Dr. Hooker passed away before the film could be made. But Baraka and Robinson persevered, and ultimately they created a scripted film funded by YouTube.

Dr. Hooker’s retellings had touched Baraka and Robinson, especially because they came from the perspective of a young girl. Robinson said that they wanted to get people “in the mindset of how complex it had to be to be a child when it happened,” noting that the basic realities of childhood—being teased, falling in love, wearing the right clothes—were still present right alongside a very real struggle to survive. “This happened to young people.”

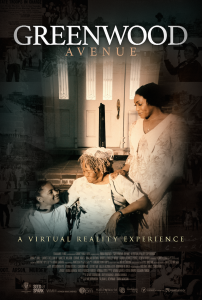

VR turned out to be a great medium for the film, which Baraka noted gives us back a “time and place that no longer exists.” Greenwood Avenue: A Virtual Reality Experience closed the centennial commemoration of the massacre and opened Juneteenth in Tulsa in summer 2021.

Even in the height of the pandemic, the film was well received, with productive and insightful post-screening commentary from people from all walks of life. Baraka and Robinson particularly loved being able to share Oculus Go VR tech with the older generations. The kits were provided by RedFlight Innovation and free for viewers in attendance.

Greenwood Avenue has been screened at several festivals, and the pair has partnered with the Oklahoma City Thunder and the Chicago Bulls, among other organizations, to put the film in classrooms. It was also on YouTube for a year to make it accessible to all teachers.

“We see film as an empathy machine for people to position themselves to love each other and ourselves better,” Robinson said. And you can expect both of these talents to keep spreading the love. Currently they’re working on a best-friend road-trip film set in Northwest Arkansas, and Baraka has some—still secret—documentary and series work coming up later this year. We can’t wait to see what they have in store.

Comments