LETTERS TO FRIENDS + STRANGERS

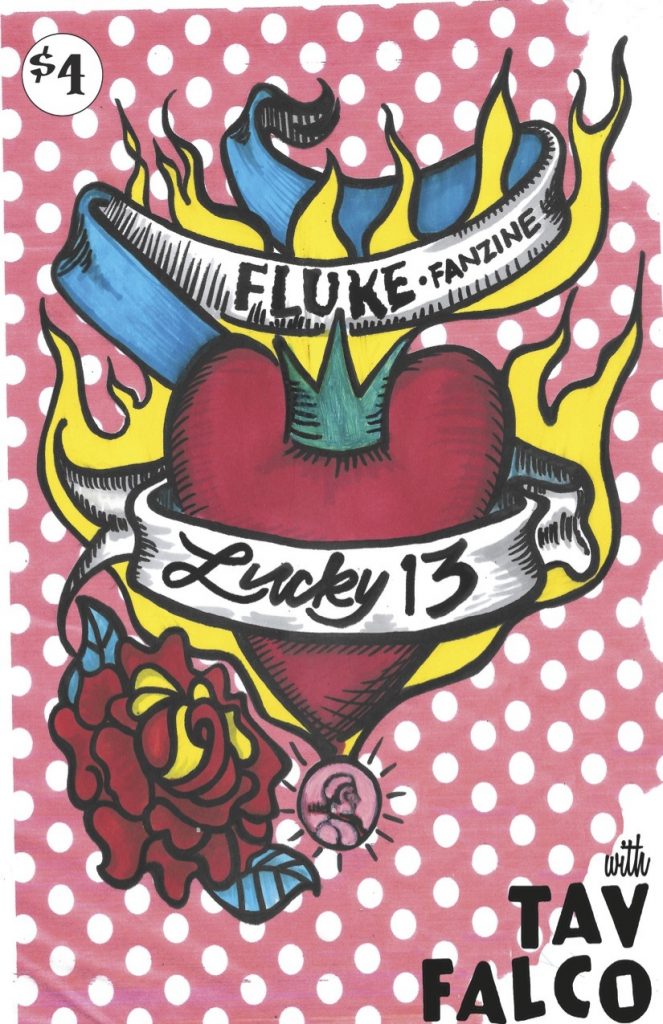

Thirty years ago, Matthew Thompson started a zine with two friends called Fluke. Today, it is still going strong.

WORDS / KODY FORD

PHOTOS COURTESY / FLUKE FANZINE

Zine culture goes back decades, if not centuries. One could argue that Thomas Payne’s Common Sense was an early example of zine. In the 20th century, they grew out of early sci-fi fandom and eventually spread to topics like feminism, horror stories, and, most notably, music. Early music zines like Crawdaddy! and Mojo Navigator Rock and Roll News sprang up in California. Punk rock’s DIY aesthetic was a perfect fit for zines. British fanzines like Sniffin’ Glue and Bondage spread the word to the world of what was happening in the UK punk scene. Throughout the 1980s, zines spread across other genres such as hardcore and even mainstream rock with multiple Bruce Springsteen fanzines popping up. So, as Little Rock’s DIY and music scene grew during the ’80s and early ’90s, the emergence of zines was a natural progression of the cultural development happening.

One such zine was Fluke. Created by Steve Schmidt, Jason White and Matthew Thompson in North Little Rock. Its origin was a bit serendipitous according to Thompson. Schmidt had graduated high school and was living with his mom and working at TCBY Frozen Yogurt in Lakewood. A homeless man would come in and write the numbers one through twenty-seven on a piece of paper, continuously. At the time, Schmidt figured the man was teaching himself to count, which inspired Schmidt to take action in his own life. He soon began hosting a punk rock radio show on KABF, joined the band Chino Horde and started a fanzine.

In the summer of 1991, the trio launched Fluke 1. Schmidt interviewed touring bands Fugazi and Plaid Retina, who performed at what is now Vino’s on 7th in Chester in Little Rock. White interviewed Tim Lamb, who published a Little Rock fanzine called Lighten Up in the ’80s. Thompson was taking a writing course at UALR and one of his assignments was to write a letter to the editor of the Arkansas Gazette. His letter addressed the correlation between violence on television and society. It was printed in the paper so he included that in the first issue, as well as other writings, photography and record reviews. Their friend Colin Brooks worked at Kinko’s on JFK and McCain in North Little Rock and he assisted them with printing the first two issues.

Growing up, Thompson says zines were crucial to the community.

“I think zines touch people on an intimate level because it is a personal piece of literature and art and people feel connected to that.” He added, “They played a vital role in the scene. Fanzines were the glue that held it all together. They offered information, opinions, insight, journalism, art and dialogue between friends. By 1992, there was an influx of local zines in Little Rock. It seemed like everyone and their dog did a zine.”

For Thompson, zines gave him a way to contribute to the scene as a creator. He took what he learned in high school journalism classes and applied to Fluke. He believes the punk rock bible Maximumrocknroll—which began in the Bay Area in 1982—and Ahoalton—a zine on punk rock and Native American culture by Little Rock native Mark Dober—were among the first zines he ever encountered. He would read reviews of other zines in the back pages of Maximumrocknroll and order them. Some of Thompson’s favorite Little Rock zines of the late Eighties/Nineties include Jeremy Brasher’s Risk, which touched on train-hopping; Theo Witsell’s Spectacle; Jim Thompson’s Handout; and Sam Caplan’s Tracks n Macks.

Thompson cites John Pugh’s Eyepoke and Get Lost as his absolute favorites of mid ’90s Little Rock zines. Thompson said, “John was everywhere––in the streets, at the shows, at the punk houses, copy shops, traveling, and documenting it all[…]There were a lot of great Little Rock zines in the early ’90s and a lot of not so great ones, too. That didn’t really matter, though. It was something to create and engage your friends with.”

Fluke has brought many memories for Thompson over the years. The highlight has been “being able to connect with people I admire and am inspired by.” He befriended musician Mike Watt, Arkansas artist buZ blurr, and musician and zine creator Aaron Cometbus. He met Arkansas expatriate musicians like Tav Falco and Gary Floyd. He handed copies of the magazine to rock legends Iggy Pop and Keith Morris. Last year, Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore even ordered several issues. These, of course, are not the only reasons he has kept the zine going for all these years.

“It energizes me. People interest me. It’s a fanzine, a zine for fans. I’m a fan of music, art, writing, photography, ideas. It’s something I am passionate about,” Thompson said. “Fluke connects me to the world. I took two long breaks––seven and four years––battling addiction and then piecing my life back together. Fluke has given me purpose in life.”

Many Fluke contributors have gone on to do big things. Fluke co-founder White has toured the world as a guitarist for Green Day for over 20 years now. Brooks played in Dan Zanes and Friends, whose album Catch That Train! won the 2007 Grammy Award for Best Musical Album for Children. buZ blurr’s art has been shown in major art exhibits and museums worldwide, most recently in SFMOMA and Beyond the Streets in Los Angeles. Nate Powell’s 2008 graphic novel Swallow Me Whole won an Ignatz Award and Eisner Award for Best Original Graphic Novel. He also won a National Book Award for his illustration work for the March graphic novel by the late, great Rep. John Lewis.

Powell has collaborated with Fluke for 15 years, but he first became a fan in 1992 when he picked up Fluke #2 along with some other local zines. The DIY movement inspired Powell to collaborate with his friends Mike Lierly and Nathan Wilson to self-publish their own comics. In 2006, Powell and Thompson reconnected when Powell contributed illustrations for the booklet accompanying the documentary, Towncraft, about the Little Rock music scene of the late ’80s and early ’90s That was immediately followed by Powell’s cover art for Fluke #7, and they have been regular collaborators since then, roughly once a year. Powell cites Fluke and zine culture as having a major influence on his career to come.

“Zines were one of the most accessible forms of self-expression for teenagers in the 1990’s underground, and there were at least a dozen zines being published by young people in the Little Rock area,” Powell said. “D.O.A., the dystopian superhero comic we self-published starting in 1992, was made possible by the proof-of-concept established through other kids’ zines, and by 1994, I was making more personal zines of my own, eventually folding comics back into the zine content later in the ’90s and ultimately arriving at my current mode of full personal and political expression through my comics.”

Fluke also provided a way for people to stay plugged into their hometown scene in the days before social media and widespread Internet use. Cora Crary, a Little Rock native who left for the Pacific Northwest in the early ’90s, used the zine as a means of connection.

“I left Little Rock in the fall of 1990 and other than living in town for a few months in 1992 and 1994 I wasn’t really around, so for me Fluke contributed to my understanding of what was happening in Little Rock,” Crary said. “That said, Fluke came about at a time in the scene where everyone had zines, since especially if you weren’t in a band, a zine was essentially a calling card, as well as an excuse to ask your geeky questions of the creators you followed. Fluke has persisted all these decades and has provided a through line connecting the Little Rock scene that we grew up in with all the new and adjacent projects made or inspired by those in the scene.”

Over the years, production has evolved. Instead of printing and assembling the zine at a copy shop, Thompson now has a printer who prints and collates Fluke. Instead of printing 100 or so copies, he now prints 1,000 or more and sells them in stores around the country and even abroad. He has slowly but surely built up a distribution network across the country by taking the time to develop personal relationships with people and stores. Some stores have sold Fluke since its inception, but Thompson is always looking for more outlets worldwide to carry the zine.

Last year, he started Fluke Publishing––printing and distributing magazines created by friends.

Powell credits Fluke’s longevity to Thompson’s growth as a creative and a person.

“I think it’s essential that zinemakers grow older with their publications, allowing shifts in their own personal interests to coexist with a sense of continuity,” Powell said. “Fluke excels in this by focusing on musicians and artists who have grown and evolved alongside their creations, and Matthew takes care to highlight this in a very open, sincere way.”

Crary sees the zine as an inspiration. She said, “Zines have an intimacy and immediacy to them. Publishing and communications have changed dramatically since the first Fluke was released, but the format remains as relevant as ever […] Fluke has been a love letter to a scene that taught us all that if you don’t see what you’re looking for, then maybe it’s time you make it yourself.”

In late 2019, Thompson curated the “Fluke Life” art show in North Little Rock. Gen X’ers, Millennials and Gen Z’ers packed into Dedicated Visual Art Studio & Gallery in North Little Rock. Patrons browsed through reprints of back issues and bid on skate decks painted by Arkansas artists like Milkdadd, Olivia Trimble and Michael Shaeffer.

“When I was approached to create a deck, it was a no-brainer,” Shaeffer said. “Fluke has been such a huge part of Central Arkansas culture for as far back as I have lived here. It has always been a zine that would celebrate not only interesting music and art on a national level, but also celebrate cool things happening in the area.”

The skate decks were manufactured about a mile down the road from where the show was held. Paige Hearn, who has made skate decks in Levy since the ’80s, provided the boards. Gallery owner Jose Hernandez helped recruit artists from across the state. The age range of the artists ran the gamut with buZ blurr and Kuhl Brown being the oldest—in their 70s and 80s, respectively—and the youngest was Thompson’s daughter, who was 13 at the time. She was the only artist not from Arkansas, but he made an exception.

Thompson said, “It came together seamlessly, really. Everyone was, pardon the pun, on board to be a part of the show. It was absolutely incredible and overwhelming, the place was packed inside and out for the whole night. It felt like a homecoming of sorts, so many friends I’ve had for decades showed up, as well as people I’d never met. Jason [White] was in town for the holiday so he showed up, too. It was one of the best nights of my life, honestly. I hope to do another one in November, if things calm down with the virus.”

The future of Fluke looks bright. Thompson plans to continue publishing the zine to grow his audience and will even release a book of his own this year. His love of zines has not wavered even as the magazine enters its 30th year.

“I found Fluke to be a project that propels me.” He added, “I love how the magazine drives itself and I’m just along for the ride. One idea building on another. I enjoy collaborating with others. Once it is created, I love sending it out into the world––through mail order and to shops that sell zines. Secretly, my magazines are actually letters to friends and strangers.”

If fans would like to order copies, please visit www.flukefanzine.com. Send mail to: Matthew Thompson, PO Box 1547, Phoenix, AZ 85001.

IG / @FLUKE_FANZINE

Comments