An Excerpt from TWENTY ACRES: A Seventies Childhood in the Woods

By Sarah Neidhardt

A young leatherworker named Larry drove into Colorado Springs in the early summer of 1972, a year after my parents were married, from a far-off place called Fox, Arkansas. He and Daddy met through mutual friends at a leather shop near the bookstore where my parents worked. Over beer and joints, Larry extolled the glories of the Arkansas Ozarks: the caves, the music, the swimming holes. Daddy had looked at land in southern Colorado—all he could afford in the state, and the location of the first commune in the US, Drop City, among others—but it was dry and grim. He only knew of Arkansas as hillbilly country, but according to its license plates at the time, it was the Land of Opportunity and anything but dry. And Larry painted a back-to-the-land utopia with his stories.

A young leatherworker named Larry drove into Colorado Springs in the early summer of 1972, a year after my parents were married, from a far-off place called Fox, Arkansas. He and Daddy met through mutual friends at a leather shop near the bookstore where my parents worked. Over beer and joints, Larry extolled the glories of the Arkansas Ozarks: the caves, the music, the swimming holes. Daddy had looked at land in southern Colorado—all he could afford in the state, and the location of the first commune in the US, Drop City, among others—but it was dry and grim. He only knew of Arkansas as hillbilly country, but according to its license plates at the time, it was the Land of Opportunity and anything but dry. And Larry painted a back-to-the-land utopia with his stories.

A few days later, Larry’s car was stolen; in Fox fashion, he had been leaving it unlocked with the keys dangling from the ignition. He now had no way to get back to Arkansas. Seizing the chance to observe Arkansas’s bounty, Daddy and his climbing friend, Ray Connor, drove Larry back home in the summer of 1972 with a reticent Momma and six-month-old me in tow.

We spent a night with a folksinger and dulcimer maker, Judy Klemmedson, the first back-to-the-lander to come to Fox, in her old, rundown farmhouse in the woods. She had no electricity, and only candles lit the night. A deafening cacophony of night creatures emerged in the utter blackness and spooked Momma as she lay me on a sleeping bag on a rough wooden floor. I woke in the middle of the night screaming inconsolably. Momma groped for me fearfully in the dark, unable to see even her own hands. She was terrified. She always reminds me of this story: “I really was frightened. I couldn’t even see you, Sarah.”

We stayed in a tent for the next few nights, and Momma recoiled at the wet heat (the Ozarks are a humid subtropical climate). Beads of sweat covered my face, neck and chest like blisters, and Momma feared something was wrong. But I was happy, and we sweltered on in the buggy sauna of an Arkansas heat wave while Daddy and Ray looked at the land.

A few days into the trip, Momma sat nursing me in our car in front of a real estate agent’s office on Main Street in Mountain View. The agent was a heavyset local woman in her sixties with a round, high puff of neatly coiffed hair. Daddy walked out of her office, opened the car door, and told Momma he and Ray had decided on a piece of land.

She stuttered that it was a bad idea. She hadn’t believed it would really happen and had no interest in living in that remote sweatbox.

“You want me to give up my dream?” Daddy protested, already lost in his plans.

Momma fell silent, looking out on the town’s sparse collection of stone facades, waves of heat haze blurring the road.

In late December 1972 or early January, in a long-forgotten whirlwind of packing and goodbyes, Daddy, Momma and I left Colorado’s cold, dry winter bound for Arkansas mud. Daddy drove a moving van towing an International pickup, both vehicles filled with the paraphernalia collected for our new life. Our co-landowner, Ray Connor, followed in a station wagon with his wife, Susan, and their baby Sunshine. We drove away from 1973 into a facsimile of the past, leaving behind wars, oil embargoes, pop culture and the nine-to-five life. The United States was amid an energy crisis, and the Colorado college town we lived in was too close to suburbia. But Arkansas lay before us with the rising sun, a promise of country roads and a bountiful farm.

I was one of the countless American children born of the counterculture revolution who spent some period of their youth living an impoverished rural life. Our parents returned to the land—a misnomer in that most weren’t going back to anything they once knew but rather to some archetypal, pre-industrial past. As many as one million Americans returned to the land by the end of the 1970s. Daddy—twenty-eight, quixotic, impulsive, and headstrong—brought us to the Arkansas Ozarks in a fever for adventure and rugged land, caught up in the zeitgeist of this back-to-the-land movement.

This is the story of that life, of a family tucked away in a log cabin of white oak on a mountain in Arkansas that gave me the formative years of my life and changed the course of my parents’ lives forever, taking them on a journey from privilege to food stamps. It is the story of an American era, strangers in a strange land, class, childhood, and memory. It is a cautionary tale and an ode to an unconventional and pastoral life.

When you delve into the stories of other back-to-the-landers, it can feel like we were everywhere, passing each other on the road to rural America with our flea-market farm tools and woodstoves and goats. But I was unaware of that, mainly feeling we were in our own little world. Although my family was part of this more significant movement that now threatens to whittle the experience into cliché, then it was just home. It was on the farm that I learned to walk. To talk. To sing. To run in woods and swim in rivers. To read and to write. To make a home. It was where I lived at an age when my environment was making an almost biological imprint, the sounds, smells and experiences speaking to my same genes.

Homemaking was the central preoccupation of my childhood. I was obsessed with any feature of the landscape—a canopy created by low-hanging branches, a space between boulders—that could be used for shelter. My parents were busy all around me turning a plot of land into a home: constructing walls, gardens, fences, and a pond, bringing in water and electricity, growing, butchering, cooking. I went to work creating my own little homes and corners of the wilderness to keep me dry and safe.

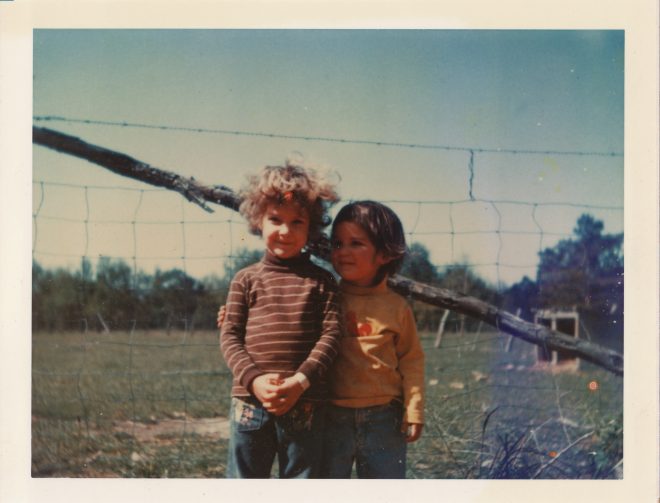

My sister and I built many playhouses over the years, with piles of scrap wood cluttering the yard from my father’s carpentry work and the building of the farm. We used old trunks and nailed boards to trees. We dug holes for toilets, not so different from the old metal kitchen chair with a toilet seat that for years my parents kept in the woods behind the house and moved from place to place—the teeming sea of bugs on the forest floor could dissolve the shit in a day (dung beetles were childhood favorites) unless the dogs or other animals got to it first. And we set up little tables and shelves in makeshift kitchens.

I watched Momma make bread, beans and butter as a toddler at her leg and then as a young girl who could have joined in. But Momma never had us help in the kitchen, where, after years of modern kitchens, she was learning to cook over wood and with all the parts of the animal. While she hauled water and stood over the wood cookstove, my sister and I went foraging to stock our own kitchens, picking shiny yellow buttercups and goldenrod and Queen Anne’s lace for our mud pies and dried yellow dock seeds for our stews. We practiced the small ceremonies of everyday life. We stirred and baked and organized our supplies just like Momma. In the heavy summer sun, we cracked eggs over metal scrap left in the yard and watched them sizzle.

Vivid images of our Arkansas land run like a half-ruined movie reel pulled out of an old box in my head—many of its parts degraded and moldy from time but others flashing clear: delicate Queen Anne’s lace gracing the sides of roads; the Old Man’s Beard tree covered in stringy, white pom-pom flowers along the winding dirt road out to our cabin, entrancing me with its name and beckoning us along towards home; and the old for-parts John Deere tractor we played on, its steel bones fading and rusting in the overgrown grass and weeds. In fact, I have an almost photographic memory of our land in my head: one distinct elderberry bush grew on the side of the main highway as it approached the tight curve at Devil’s Elbow. A purple thistle grew along the fence on the last stretch of road to the cabin and a sumac a few feet away on the north side of the fence. The fruiting body of a shelf fungus anchored itself to a tree where the west path opened to the road. A rosebush heavy with hips was down a bit from the goat pen. A pokeweed grew by the compost pile.

I kept a sticky-backed photo album labeling leaves and other plant specimens I collected. I was paying close attention to the flora and fauna around me. We plucked stunned june bugs off the screen door, and Daddy tied their fragile legs to string and threw them into the air, turning them into tiny kites bobbing above our fingers. We smeared acrid, dusty, glowing firefly bellies onto our shirts. We dug up fat white grubs—the larval stage of june bugs and dung beetles—from their parallel universe beneath us. And we smashed blood-swollen purple dog ticks between rocks like ripe berries. Details as mundane as the empty husk of a molted cicada cling to my memory as emblems of that time, magnified by a child’s ability to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary. My world was turning on one leaf, bug, conversation, and toy at a time, like lights coming on at dusk.

___

About Sarah Neidhardt

Sarah Neidhardt has worked as a bookseller, secretary, paralegal, copyeditor, and stay-at-home mother. She grew up in Arkansas and Northern California and now lives in Portland, Oregon, with her husband and teenage son. She is a graduate of Oberlin College.

Sarah was an infant when her parents joined the growing back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s. Uprooting their young family to move from Colorado Springs to an isolated piece of land deep in the Arkansas Ozarks, they built a cabin, grew their own food, and for years strove to escape their former lives and achieve an ideal of agrarian self-sufficiency.

In Twenty Acres: A Seventies Childhood in the Woods, bohemian counterculture meets pioneer homemaking. Neidhardt revisits her childhood with compassion and candor, drawing upon a trove of family letters to retrace her parents’ journey from their affluent youths, to their embrace of rural poverty, to their sudden and wrenching return to conventional society. As she comes to better understand her family and the movement that shaped them, Neidhardt reveals both the treasures and tolls of an unconventional, pastoral life.

To purchase a copy, visit uapress.com, or stop by Pearl’s Books, located at 28 E. Center St in Fayetteville.

Comments