Tracing Time: the Sculpture of Robert Lemming

WORDS / K. SAMANTHA SIGMON

Robert Lemming is an artist who, instead of looking to a past shaped by humans, looks to Arkansas’ pre-history to create abstract, yet organic, forms. The most recent work from the artist’s two ongoing, related series that he often shows together–Burrows and Fucoid Arrangements–will be shown at the Trinity Gallery in the Historic Arkansas Museum from May 13 until August 8, with the opening reception held the evening of May 13. Lemming’s unique, thoughtful, professional, and well-crafted art is the product of a lot of hard work, a little serendipity, and traces of emotional complexity.

Lemming came to sculpture in a round-about way. After graduating high school in Huntsville, AR, he attended Henderson State in Arkadephia for drawing, painting, and printmaking. Having not quite finished his degree, he moved back to Northwest Arkansas, stopped creating art, and worked outdoors. After a few years, Lemming finished his art degree at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville in 2011.

The inspiration for the work Lemming makes came when he dropped out of school and began finding fossils while working with a survey crew in very remote areas; “You end up in a lot of beautiful places in Arkansas where people that own that land maybe have never seen . . . and so there was a strange adventurous quality [I had when] I started finding these fossils that had organic patterns [with] something very lush and beautiful about them,” Lemming said. He took them to the Geosciences Department at the University of Arkansas to discover that they were fucoids, indigenous trace fossils alive when a shallow sea covered Arkansas–a type of fossil created when animals would move and their physical pathways made scrapes in the earth that created overlapping shapes.

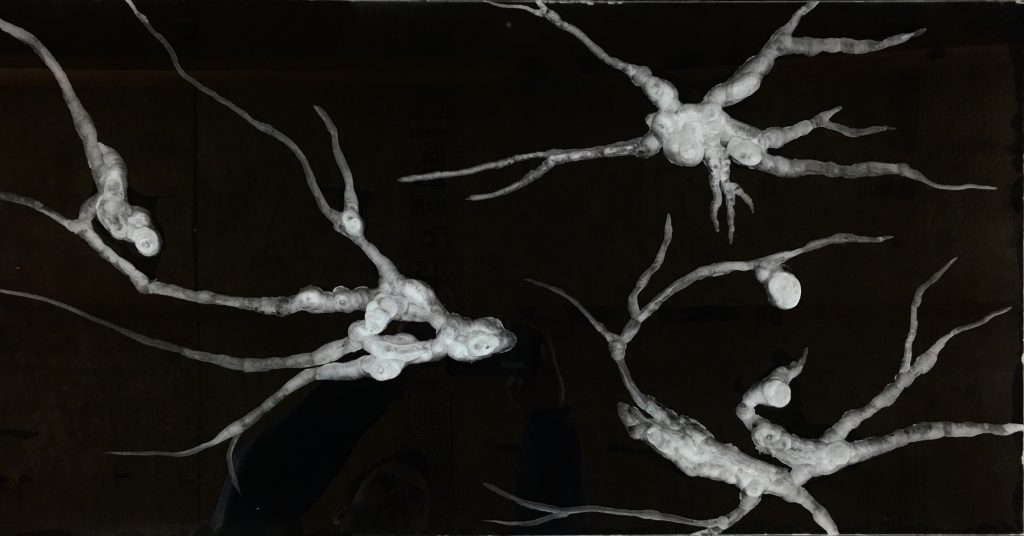

Lemming’s work, highlighted in Fucoid Arrangements, plays upon the barriers between the grotesque and the beautiful, challenging the assumption that if something is ugly, it can’t also be pretty. The animals responsible for these fossils “were bottom feeders, which seems to some people like a disgusting thing, and yet inadvertently through their very presence they have created these things that are beautiful 325 million years later by a random person finding them in the woods,” Lemming said. “What I don’t see enough of is when things get to that borderline abject state where you don’t know if they’re beautiful or if they’re ugly, and you have to kind of investigate yourself.”

To play upon this beautiful/ugly balance, the artist casts these abstracted organic forms from common synthetic materials such hot glue, an untraditional medium not thought of as beautiful, yet it becomes striking with the right touch and lighting. Lemming uses glue because it is found anywhere, translucent, and flexible, and the viewer will be able to see every moment where he retraced or reworked, laying bare the artistic process to those who look close enough.

The fossils themselves have inherent sculptural qualities that keep him fascinated while giving him a structure in which to base his work; “The best thing I could do, the most dangerous thing I could do, was to let some thing else dictate what I was doing, so by going to fossils, I can have endless, random possibilities of how I put them together and use them, but I can’t completely control it,” Lemming said. “I have to work with their limitations, so there was already a structural element that I was taking myself out of and paying homage to.”

The Burrow Series comes out of the continued interest in traces of movement–static representations of where organisms have been–but comes more directly from the artist’s imagination. In these, Lemming starts with a flat sheet of acrylic that he paints and then drills designs into, so every tool mark is visible in the final work. Coming from a two-dimensional background, Lemming see this process as drawing with tools rather than pencils or paint brushes. He thinks like a painter, but creates sculpture.

Although Lemming focuses on formal qualities of shape and color, he says emotions might be buried in his work. His sculptures seem like something integral and primal to our being, etched into us in times long before we were capable of documenting our experiences. Psychological thoughts might bubble to the surface with more time spent with this work, beyond the initial repulsion/pull gut reaction we have to seeing it for the first time. Something from a high school science class might seem familiar, something we studied invisible to the naked eye like nervous systems or firing neurons or parts of simple organisms in a shallow sea. Perhaps we see pieces of our physical selves, a kind of David Chronenbergian body horror playing on our fears of infection or injury, as we gawk like when we view specimens at a natural history museum. But Lemming’s sculptures evoke these feelings lightly, even politely, letting us come to the work in our own way.

Robert Lemming will continue investigating what lies on the surface and just beneath in Burrow Series and Fucoid Arrangements. “These both are very interesting; I’m able to find enough variety in these bodies of work,” Lemming said. “I think they’re personal enough. They’re things I don’t see anyone else doing right now, and maybe that will change, but they seem rich and I don’t feel like I’ve come to an end.”

Comments