THE BALLADEER: Neal K. Harrington creates images that are frantic, suggestive & deeply American.

WORDS / KODY FORD

PHOTO / KAT WILSON

Alligators walked among us. That’s what the sign said anyway. We walked down the Bona Dea trail, a paved path that ran alongside a marshy area kept saturated by Lake Dardanelle on the edge of Russellville. Mist hung low in the air, the remnants of the Sunday afternoon storm that dissipated less than an hour before.

Neal K. Harrington – artist, professor, father – leads the way, one curve after another as we looked for a bridge to take some pictures. He’s clad in a Trilby hat and an unbuttoned plaid shirt revealing a screen-printed image that he had designed for a poster contest. Its a bit of a self-portrait with the dominant feature being a caricature of his lush facial hair that falls somewhere between Dusty Hill and Frank Beard on the ZZ Top Scale of Man Plumage. It’s a stylish look for the moment, but one that Neal has rocked for a while. As we trudge on, searching for the perfect locale for a photo shoot before the sunlight moves past the “magic hour.”

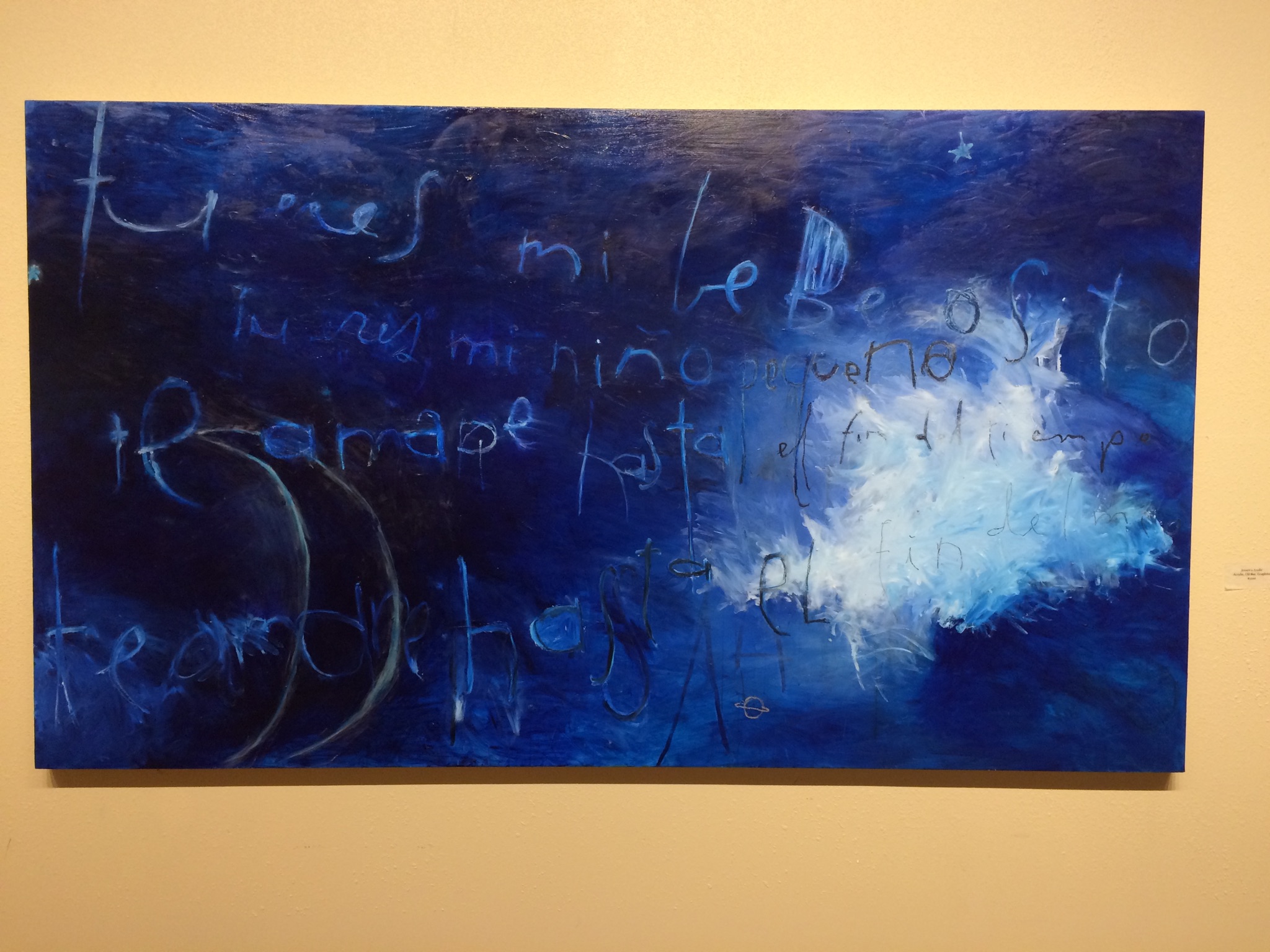

“I used to walk out here every night with my kid,” Neal says. “He wouldn’t go to sleep until I pushed him around in the stroller.”

Fatherhood is one of the topics that Neal is passionate about discussing along with music and, of course, his art. All of them intersect in ways that keep him on edge, each one demanding his love and his time. He constantly strives to give them the attention they deserve. Children came within the last decade of his life while music and art have been a part of it since his childhood.

Neal grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota, in the shadow of Mount Rushmore, only 20 minutes from the thunder of the engines in Sturgis. While he didn’t come from a family of artists, he described his mother as a “busy body,” who did cross-stitch and stained glass while working two jobs. Comic books played a major role in his development as a young artist. He was particularly drawn to the covers and drew them to teach himself, but still never learned techniques like perspective until college, something he attributes to his “hippy art teachers” lackadaisical approach to teaching the craft.

“I learned it all on my own through failure,” he says. “That’s why I tell my students really drawing is about correction. Make a mark, react. Make a mark, react. Correct it, correct it. I don’t make a mark and go ‘Yeah, that’s the one.’ Look at the Old Master’s, they’re looking for the perfect line. They’re searching with their gestures. I just learned that innately.”

Aside from art, Neal loved playing guitar and taught himself metal riffs by reading guitar tablature in the back of magazines. He found the blues through the white-boy licks of Brits like Cream and the Rolling Stones before working his way back to the Delta of Leadbelly, Elmore James and Howlin’ Wolf. Once he discovered the blues, he was hooked. “I like a lot of the upbeat blues, the shake your moneymaker stuff with the shuffle,” he says. “It has a catchy beat. I liked the stories. I enjoyed playing it.”

After high school, he went to the University of South Dakota, which was the largest university in the state, but had no illustration program. His parents supported his artistic endeavors but wanted him to just be an artist on the side. He tried various majors like pre-law, but hated them almost as much as he hated doing graphic design, which at that time was mostly type-setting in the early ‘90s pre-Adobe-Creative-Suite era. He took a painting class with a professor who was rough around the edges to say the least. The professor would openly ridicule students paintings, but after seeing Neal’s sketchbook, he announced to the class that Neal was “one of the only people who could draw in class.”

Neal painted, but found himself drawn to the social aspect of printmaking at the school. He also became intrigued with a young printmaking student named Tammy. A few years later, he married her. That was 18 years ago. Now they have two children together. After graduation, Wichita State University accepted Tammy into their MFA program. Neal traveled with her to tour the school and met with the painting professors, who recruited him into their painting program. After a year, he realized that painting wasn’t for him and decided to transfer to the printmaking program, but there was a catch. He had to continue his T.A. duties in painting and his wife would have to teach him printmaking.

“When we first met, Neal told me that he didn’t consider himself an artist,” Tammy says. “In undergrad school, he was a graphic design major and probably felt like he was just floating along, drifting without any passion for this type of art making. He eventually switched to painting and a spark emerged in him. He devoted many hours to his artwork. In graduate school, Neal switched from painting to printmaking. He was pretty nervous about this but hopeful for a smooth transition.

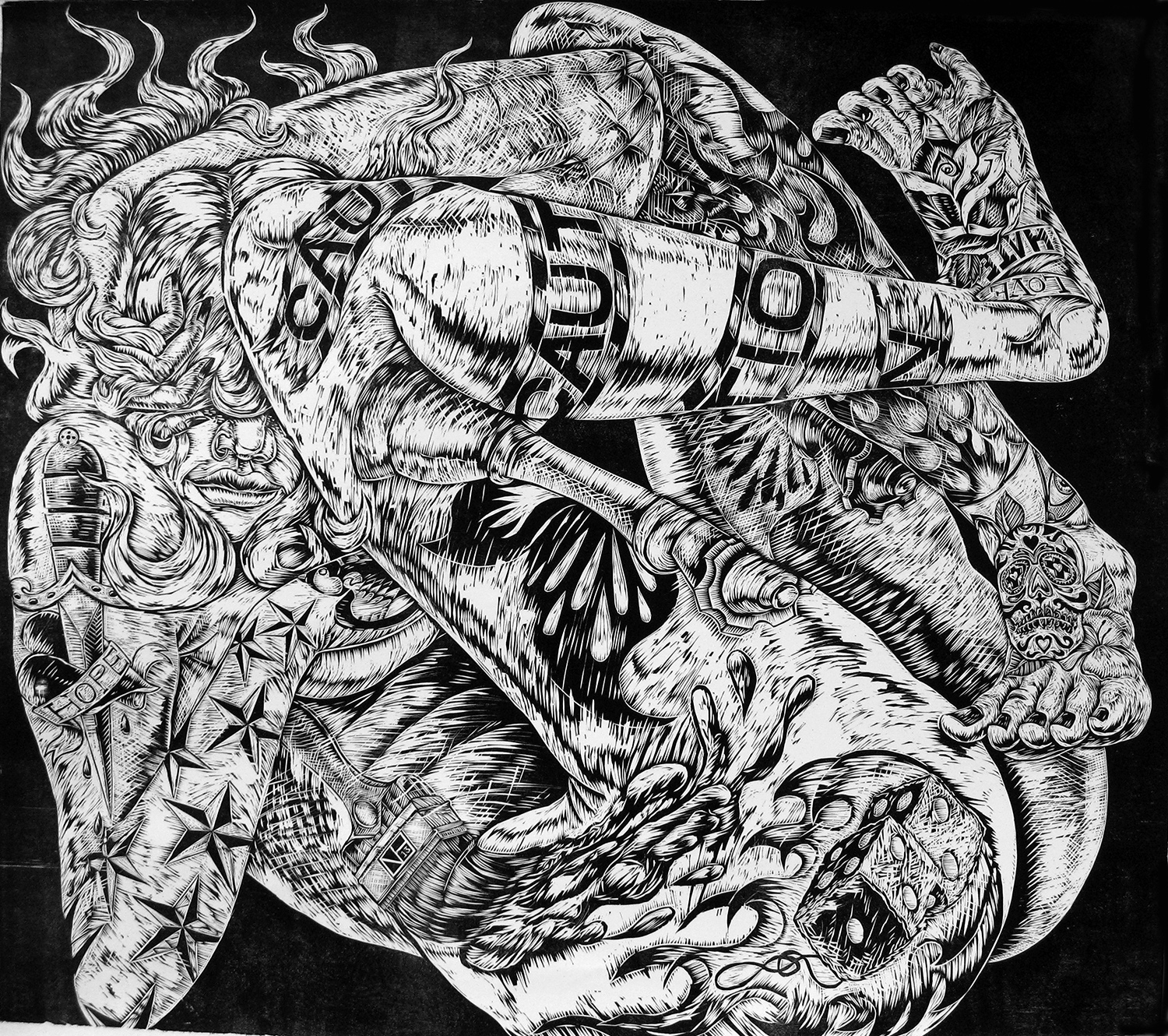

“Even though he had to re-learn much about printmaking techniques, Neal was not afraid to push the boundaries especially when it came to size. In the same year that he was reintroduced to carving relief linoleum blocks (9” x 12” size), he wanted me to order the largest pre-cut linoleum size possible. I ordered a few 36” x 36” linoleum blocks and Neal, to his credit, carved on those blocks with success. He is bold in his experimentation and in pushing scale in his work. I have never worked a 36”x36” relief and it boggles my mind to even attempt that. Neal is an artist now.”

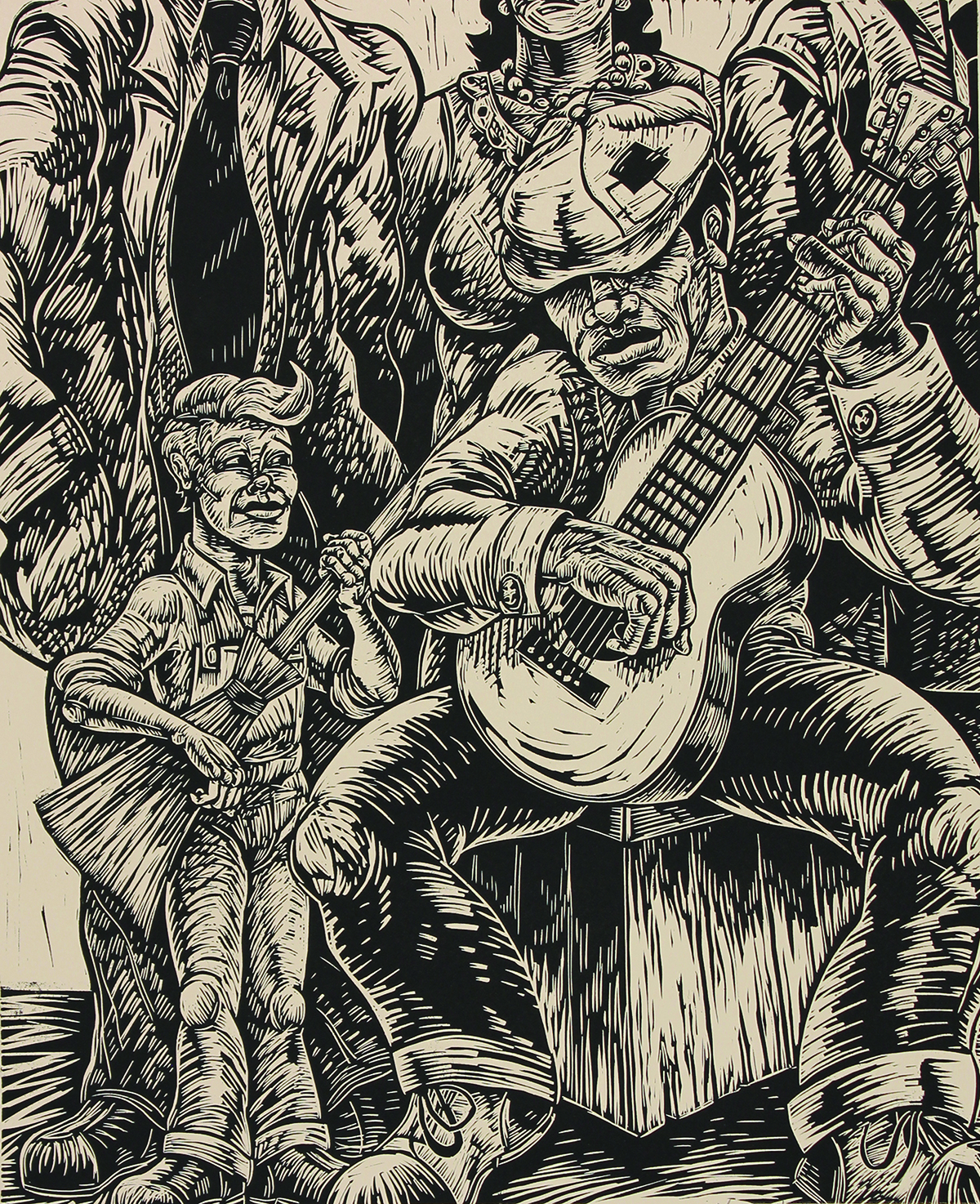

His learning curve was steep and he soon found himself teaching a class while in graduate school, often teaching techniques he had only recently learned. For his thesis, he decided to merge his love of Greek myths and music. “I felt a kinship with those stories and I swear this was before ‘O, Brother Where Art Thou’ came out,” he says. “I started doing prints that told the story of early blues, but I caught a lot of sh-t from the painters [in school] about that because I’m white and they didn’t think I should focus on African-Americans. I said I’m doing what I know and I’m trying to visually express this music because that’s what I listen to. Why should I draw a white guy playing that?”

After grad school, he began branching out beyond the blues and got into bluegrass heavily which led him into a regionalist style he describes as “R. Crumb meets Thomas Hart Benton.” He also found inspiration in Lynd Ward’s “wordless novels” such as “God’s Man,” which told the story of an artist who moves to the big city, signs a deal with a stranger, whom he later finds out is the Devil, in only 139 wooden panels.

He has created several art series such as “American Goddesses,” “The Bootlegger’s Ballad” and the “Hard Travelin’ Man.” Some of the inspiration came from the Steinbeck-esque tales his grandfather told him about the Great Depression and their nomadic lifestyle of constantly searching for work.

“It’s these self-reliant backwoodsy dudes and what went on at that time–could be a distant time ago or current and they’re just poor,” he says. “I just think about him and that time period and the crazy sh-t that went on. Ghost stories and booze and violence. I just kinda let my imagination wander and think about that self-reliant culture and what they went through.”

“It’s these self-reliant backwoodsy dudes and what went on at that time–could be a distant time ago or current and they’re just poor,” he says. “I just think about him and that time period and the crazy sh-t that went on. Ghost stories and booze and violence. I just kinda let my imagination wander and think about that self-reliant culture and what they went through.”

While developing his works, which he calls “visual ballads,” Neal starts with a premise – sometimes it’s as simple as an object like a birdcage or an ax – and tries not to overthink things. “The story comes from the view/listener,” he says. “I set up situations/events that have elements of a story but the viewer will bring their own baggage to the work.”

Though his newer works don’t always include musical instruments or equipment, he still employs musical elements such as rhythm, repetition, and textures. Over the last few years, he has collaborated with his former student, singer/songwriter Adam Faucett. “I knew him before the beard,” Neal quipped. While in class, Neal encouraged Adam to pursue his music and promised him that if he ever made an album, Neal would do the artwork. Adam brought him rough sketches for the covers of his albums “The Great Basking Shark” and “Blind Water Finds Blind Water” and they developed it further with Neal’s hand creating the finished product. Adam describes Neal’s work as “legitimate, important, neo-folk art.”

“He does beautiful work,” Adam says. “It’s deeply American. The subject matter is so relatable in a fantastic, Americana kinda of vein. The amount of detail and obvious man hours that goes into the large wood cuts he does is just daunting. There’s so much going on beyond the subject matter of the picture. You can see the inner-workings of the artist himself. They’re so busy you can see the process in a weird way. It’s automatically recognizable and even though it looks so classic, it has this earthiness to it. It’s gritty. Often the busyness of the line work in it seems almost frantic, unnerving. No one is doing what he’s doing, definitely not on that talent level.”

Adam says he wants to work with Neal for more album covers in the future. “I’ve sorta branded my stuff off of it,” he adds. “I’ve got that Neal Harrington look now.”

In 2013, Neal also created the storyboards for the Miller Brothers highly-anticipated debut feature film “All the Birds Have Flown South.”

One of the highlights of Neal’s career is winning the Delta Award at the Arkansas Arts Center’s prestigious Delta Exhibition 2013. He will also be showing his work at this year’s show. Currently, the Cantrell Gallery in Little Rock represents Neal. He first came to their attention after having his work showcased in the Delta exhibit.

“Neal Harrington’s art is special because it tells a story,” said Cindy Scott-Huisman, co-owner of Cantrell Gallery. “There is clearly some kind of storyline that would go with any piece I’ve ever seen of his. It draws you in, to look at the details because you want to know more about what’s going on in the piece and once you start looking at a piece more carefully and you stop and think about what all went into the making of the piece, you fall in love.”

These days one of Neal’s biggest challenges is balancing his work life of teaching at Arkansas Tech University and running their student gallery with being an artist and a father. “After teaching all day, maybe running the kids to ballet or baseball, then I’ve got to come home and do art,” he says. “Let’s say I get in an art show, which is great. You’ve got to get it in 2 weeks. Now I come home and I’ve got to build the box to ship it in and now I’ve burned 3 hours I could have been drawing or playing guitar. So I’d love an assistant to build my boxes or something, but I also want it done right.”

Whether it’s a late night stroll around an alligator marsh or sweeping the floors of the Norman Hall Art Gallery or chiseling away on a giant wooden slab in his basement studio, Neal gets the job done. It’s the sort of work ethic that would have put a smile on the weathered face of those working-class men in his work. And while he could have done graphic design or stuck with painting, he doesn’t regret his chosen medium of printmaking.

“They sell paintings that elephants make,” he says. “Elephants don’t make prints.”

VISIT: NEALKHARRINGTON.COM

Comments