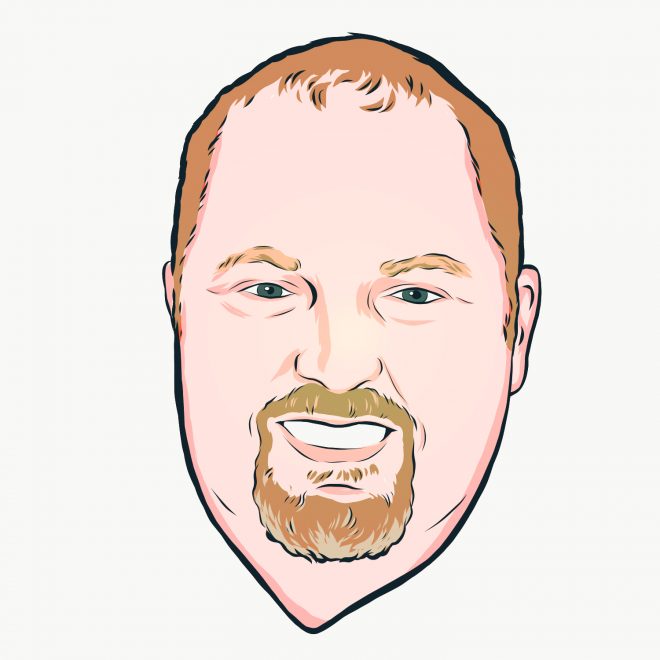

THE LEGACY ISSUE: The Songwriter

El Dorado native Odie Blackmon bought his first guitar in high school. Within a few years, he found himself in a country band in Los Angeles before moving to Nashville to make his mark as a songwriter. Through years of grind, he broke through on Music Row and penned hits for George Strait, Gary Allan and LeeAnn Womack. These days, he’s focused on teaching the craft to a new generation of songwriters.

What was the first song that you ever heard growing up that made you just think “I want to do that”?

I can’t say that there was a song that made me think I wanted to write songs as a kid, but I can say that I was naturally drawn to songs. Like when I was really young in particular “Delta Dawn” by Tanya Tucker and “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World” by Charlie Rich. I thought they were really great. And I’m talking like five years old. And then also, maybe my first awareness of songwriting was The Mac Davis Show. Before he was a movie star and he was a country artist and had written songs, but he had a variety show. During part of the show he would walk out into the audience and somebody in the crowd would introduce themselves and say where they’re from or what they did. And Mac would make a song about him right on the spot, and it was usually kind of funny. And I just thought that was the best thing.

And oddly enough, through the years … I ended up being pals with Mac and writing songs with him. And he kind of spoiled a secret. He told me that you know, the producers would go out in the lines where the people were waiting to get in during the day and, and have people fill out note cards and then they would take them back to Mack and he’d pick some out. And so he had a few hours to come up with something. It wasn’t quiet on the spot, but that was a real neat part of his TV show that influenced a lot of songwriters.

Let me say this, too. That I grew up with my mom and uncle’s 45 records from when they were teenagers. And I was very aware of The Beatles from an early age because of that and thought they had good songs.

How old were you when you started, like when you picked up the guitar and started writing?

I started writing lyrics to other people’s melodies and stuff when I was about 13 or 14. My old man gave me a little money to get a suit for graduation. I was supposed to go to JC Penney’s to buy me a pair of slacks and a shirt or something. And when I got kicked out of the Senior Follies for skipping school, I just decided I wanted to do something I wanted to do. And I took that money and went and bought a guitar at Parker’s Music. It was right around April or May of my senior year of high school. I was 17. And that’s how I started learning to play [and]…as soon as I knew enough chords, I started trying to write some songs.

What was the first song you wrote that you were proud of?

When I lived out in Los Angeles, I had gone to see Dwight Yoakam do an acoustic show at The Palace in Hollywood. And it wasn’t his normal band. It was like more of a rockabilly, bluegrass kind of acoustic set up. He did a Bill Monroe song called “Can’t You Hear Me Callin’?” And I didn’t know that was a Bill Monroe song … I liked that it was real hillbilly, but Dwight kind of rockabilly … And from that, in my mind from hearing it that night, I kind of copied it. Didn’t rip it off, but borrowed from it and turned it into a song I wrote about being out in LA and being disenfranchised and being from a small town and feeling kind of, you know, wanting to get the hell out of there. It was called “Adios, Farewell,” and it was a song basically about a Southern guy not fitting in [out] in LA.

Why did you leave L.A. for Nashville? What was that transition like?

I was playing in these bands out in LA and the Rodney King riots happened. I was living there in Hollywood and that was real scary. And it was all around us. It was buildings burning around us. Helicopters flying over people. People looting. We were basically locked up in our apartment for three days. The mayor had shut the city down. So if you were out on the streets, you were breaking the law…And it was just crazy, you know? [My friend] Jan Buckingham had been encouraging me to go to Nashville if I was going to be a songwriter. And I’d already didn’t really like L.A.—it’s such a hard place to live, Hollywood is, when you’re a broke musician, you know. Although I wouldn’t trade any of those experiences.

So anyway, after the Rodney King riots, that was enough to scare me and another buddy that was playing in bands, Mike Waldron. We said, “Man, let’s get out of here.” So a month later we packed up our shit and drove to Nashville. [We] got us a three-month lease on an apartment…got our utilities turned on and I had like 25 bucks each to our name. And we have a card table and two chairs.

[M]y mentor out there in California went to high school with a guy named Byron Hill, who was a hit song writer. And so I called and I told him I’d come to town…Byron met me at the old Pancake Pantry…and when the waitress came over, he introduced me to her name and said, “Joyce, Odie’s a songwriter who just moved to town this last week.” And she told me that they fed songwriters there that were hungry and that Kris Kristofferson had swept the floors at the studio across the street years ago, and if I ever needed a meal, come see her and I could wash dishes in the back and they’d feed me. And that was my introduction to Nashville. And…many years later, I wrote a number one hit with Byron called “Nothing On but the Radio.”

You’ve written some songs for George Strait. How was that experience the first time?

It was like it was on hold for months. Then he was in town recording and Nashville’s all a buzz and George Strait’s in town and everybody’s calling musicians are calling the songwriters, telling who’s got cuts. George just kind of comes in and goes, “I think we’ll do this one today” or whatever…So I waited a whole week for news every day. And the last day he had one song to cut and he had four left in the pile. So it was kind of nerve wracking but he cut it. So then it was going to be on the record. And I went home to Arkansas. I knew the release date and me and my mom and my grandma and my aunt went to Walmart and saw them open the box and pull out the George Strait records to put on the shelf. And I was there to get buy one with Mamaw and mom and Aunt. And so she started going, “He wrote a song on his CD everyone!” But getting to go there with my mom and my grandma and open it up. That felt great.

What are the essentials to a good song?

First off, what’s a good song? There’s different types. Some songs are poetic and have a lot of meaning. And then some songs just make you want to dance and have a drink and both are valid. I would say though that a simple sing-a-long-able, catchy melody, that’s redundant enough that you can catch on to it, but not so redundant you get bored of it. Lyrics that are not too generic but make you want to care and be memorable, but not too poetic and flowery that they lose a listener…It’s a balance between everyday language and poetry…I have a friend that says, “A song’s gotta hit you in the head, the heart, the loins or the feet.” And I believe that.

What are some things about songwriting people probably don’t realize?

How much work it is and how many hours have to be put in…If you write a hundred songs and one is great, like really great and that’s pretty good odds, man. People don’t realize how much crap you have to write just for the stars to line up to write something that is really great. For me, the marker is can it have integrity and be commercial as well? And can it be timeless and timely? Can you write something that means something to you, but it also touches other people and people don’t realize the work you have to put in. It’s not something that you fall into. It’s something you learn by instinct, and the only way you can get those instincts are by doing it over and over and over again. And I can tell you as someone that spent over 20 years showing up every day and trying to pull stuff out of thin air, that’s not easy to keep that creative fire going when you’re working at that kind of level. And when people are paying you money and betting on you, you’re showing up and you’re working. It’s not just like people sometimes hanging out. It’s a craft. You’re like a journeyman craftsman.

These days you’re spending more time in the classroom at Middle Tennessee University and Vanderbilt University teaching students songwriting. What are some lessons you’d relate to aspiring songwriters?

I would tell young songwriters a few things—the whole idea about drugs or alcohol inspiring creativity is a total myth and a total dead end road. And I think there’s a lot of older creators that will tell you that. Then I would also say that people should do this because they love music, not to get rich or become famous. And that fame, and people that are in that kind of world—that’s not really as great as people think it is. The whole goal should just be if you love music and you’re eat up with it and there ain’t anything else you could do, you should do it.

Another thing is that everybody doesn’t have to make a living at it. Music’s a beautiful thing, like the lady that plays piano at the church on Sundays and loves to do that. That’s a beautiful thing too. I have students at Vanderbilt that are chemical engineers and they’re gonna have a wonderful career doing that. They’ll always have music to do as well.

[Songwriting] is a selfish endeavor. You basically got to give up living in the town where your family is and everything you’ve ever known. And everything else is going to take a back seat to it if you’re really gonna do it in a way that’s going to get you anywhere. It’s not easy, but it’s a beautiful thing to see somebody devote their whole life to a melody with words and wanting to communicate to people like that. And that’s really all it is—sharing our lives and our experiences and communicating. And so it’s an honor to help people do that.

Comments