John-Michael Powell on filmmaking and his latest VIOLENT ENDS

(An abridged version of this interview appeared in the our Film Issue.)

Arkansas native John-Michael Powell has helped create award winning feature films, commercials and music videos, many of which have played networks, film festivals and theaters all over the world. He has worked as an editor on award-winning films and television shows. In 2022, Powell won the Audience Award at Filmland: Arkansas during the Arkansas Cinema Society’s annual Filmland for The Send-Off, his debut feature as a writer/director. This award came with a grant from industry leader Panavision. He utilized this grant when he returned in 2024 to film his follow-up Violent Ends. He worked with local crew and some local cast while shooting the film across Northwest Arkansas.

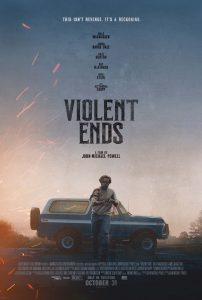

Violent Ends is a Southern revenge thriller about star-crossed lovers set against the backdrop of the Ozark Mountains. It chronicles the life of Lucas Frost, an honest man raised in a crime family whose only legacy is violence. IFC will release the film October 31st nationwide. The Arkansas Cinema Society will host a Sneak Preview screening on October 30 at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts. Tickets can be found here.

What made you want to make a film in Arkansas?

Growing up in Arkansas, I was always inspired by the people and textures of the state. I knew that when the time came, I wanted to make a film set there. In film school, I saw David Gordon Green’s George Washington, which had premiered at Sundance a year or two prior. That film had a profound impact on me. It was the first time I became aware of a Southern filmmaker telling deeply human, distinctly Southern stories. Then, right after I finished school, Jeff Nichols released Shotgun Stories. Those two films—and David’s All the Real Girls—ignited my desire to embrace my Southern roots and tell Arkansas stories. Another key influence was the writing of Cormac McCarthy. I’ve long admired his novels, and when the Coen Brothers adapted No Country for Old Men, it galvanized me to take all those inspirations and channel them into one hard-nosed, romantic, violent Southern tale.

What was your role beyond directing (e.g., writer, producer)? How did wearing multiple hats shape the experience?

I wrote, directed, and edited the film. Having worked as an editor for many years, I naturally approach filmmaking through that lens. Editing shaped how I see performance and how I shoot. I’m not a David Fincher type who shoots 99 takes. I know what I need, I get it, and I move on. If something goes wrong on set, I can re-edit the scene in my head and adjust our coverage on the fly. If you want to direct, learn to cut.

What was the biggest challenge you faced during the production of Violent Ends and how did you overcome it?

What was the biggest challenge you faced during the production of Violent Ends and how did you overcome it?

We learned we were fully financed and ready to go two days before the SAG strike in 2023. We were up and running for exactly one day before shutting back down. The strike began in June; our start date was set for October. We applied for the SAG independent waiver—the one that allows productions to work with SAG actors during a strike—on the very day applications opened. We assumed it would take a few weeks to be approved. After all, we had one financier and no ties to any studio, which was the key prerequisite for the waiver. But weeks turned into months—months of torture. We called SAG every day and got nowhere. By September, we still didn’t have the waiver. We set a drop-dead date—let’s say it was a Friday—when we’d have to push the film to the following year. Miraculously, the waiver came through that Wednesday, just two days before the whole production would have collapsed.

But now we faced another challenge: we had to cast the entire film in four weeks. By SAG rules, we couldn’t even approach actors before getting the waiver. Casting a feature in a month, with actors spread across New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta, New Orleans, Dallas, and Arkansas, was beyond stressful. But our casting directors, Lindsay Graham-Ahanonu and Liz Coulon, saved the production.

What surprised you the most when directing this film?

This was my first time working with name actors—people who’ve worked with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Greta Gerwig, Sam Mendes… and then there’s me, some guy with a little story set in Arkansas. I worried they wouldn’t respect me, and honestly, I wasn’t sure I had what it took to collaborate with such a talented cast. But I quickly learned that wasn’t the case. Not only was I up for the challenge, they were the most collaborative, supportive, and generous group of artists. They brought their wealth of experience to set and helped guide the story. They reminded me we’re all just storytellers—and that a good story is a good story.

Did anything go completely differently than you expected for better or worse?

We were lucky that most things went as planned. The biggest changes came with locations. For example, we had scripted a scene at a high school baseball game. While scouting, we passed a dirt racetrack near Van Buren and decided to stop in. The owner was immediately on board, even offering to rally all his buddies with race cars for the shoot. So what was originally a baseball game became a stock car race. Sometimes, the unexpected plays in your favor.

What was the most rewarding part of the process? Any specific moments on set, in post, or even at a screening?

I still haven’t screened the film publicly, and since we shot it in the fall of 2023, I’m dying for people to finally see it. But the most rewarding part of the process was working alongside my cast and Arkansas crew, who were incredible. A personal milestone was getting to do the sound mix at Skywalker Ranch in Marin County, California. Spending a week there finishing the film felt surreal. We were even invited to screen it at The Stag Theater on the ranch, which is considered one of the best-sounding, best-looking theaters in the world. Showing the film there for Skywalker employees was a dream come true—an experience I’ll probably never replicate.

How did you find and work with your cast and crew? Any lessons on collaborating?

As I mentioned, our casting directors assembled a cast that was deep in talent. One of the biggest lessons I learned was how much actors value the text. As the writer, I can be a little flippant about words—they’re just ideas that flit in and out of my brain, and after ten thousand readings, they lose some weight. But I came to appreciate how seriously actors take the script. It seems obvious, but when it’s your own work, it’s hard to see it from their perspective. I also learned to let actors “roll around in the mud”—to let them play. If you want the best performances, give them room to explore.

What was your approach to visual style or tone? Did that evolve during production?

What was your approach to visual style or tone? Did that evolve during production?

I spent a lot of time prepping the visual language of the film, pulling references for nearly every moment and collecting key images for photography and production design. My cinematographer, Elijah Guess, and production designer, Christian Snell, worked closely with me to craft the look and feel. We aimed for a classically tense style: composed, methodical photography, lots of dolly moves, and a palette that captured the tension of autumn in Arkansas. Once we got into production, much of that classical approach shifted to Steadicam out of necessity. Shots we had planned as four separate setups became a single oner. Nick Serabyn, our Steadicam operator, would hear us say, “Okay, you’re filming the whole scene in one take—go!” That constraint ended up defining the film’s visual language and gave it a distinctive energy.

If you could go back and give yourself one piece of advice before you started this project, what would it be?

I’m going to cheat and have two bits of advice. One is practical, the other is philosophical. The practical advice for first-time filmmakers: plan all your shots, then figure out how to tell the same story in half as many. On the day, the sun will set faster than you ever imagined—it’s some kind of cruel magic the film gods play on filmmakers. So simplify your shot list. It’ll take a load off your shoulders and let you focus on directing instead of editing on set.

My second piece of advice is more philosophical: your job as a director is to hire great people and then let them do their jobs. You can’t carry the weight of every detail, every paint swatch, every tripod. Trust your team. From the actors to the key grip, if you’ve hired the right folks and let go, you’ll have more time and space to learn how to be a director. That should be your main goal for your first feature—to give yourself room to grow into the role. You can’t grow if you’re juggling everything.

How has this experience shaped your vision for future work? What’s next for you?

As soon as I walk off set, I’m already thinking about how I want to approach the next production differently. I like to experiment, so I don’t see myself staying in one genre box. Violent Ends is a revenge tragedy—dark, dramatic, emotionally heavy. Now I’m drawn to making something lighter and more fun. I recently finished a draft of a dark comedy crime story set at a rural motel with a supernatural twist. People might read it and not even connect it to the filmmaker who made Violent Ends. I’m also working on an adaptation of a very well-known author’s book—a black comedy fantasy about angels, demons, and their roles in guiding humanity toward light and darkness. Again, it’s a total departure.

Whatever comes next, I want to push my visual language as a filmmaker. When people ask me what my style is, I say I have no earthly idea—maybe I’ll figure it out in three or four more films. Maybe I never will.

Comments