A Celebration of Black Country Music

The sounds of twang and laughter filled The Willard and Pat Walker Community Room at the Fayetteville Public Library Sunday, June 30 for the Black Music Month Celebration.

The program began with a welcome from Northwest Arkansas morning anchor Randy Wilborn as he introduced the starting screening: a trailer for “Bad Case of The Country Blues: The Linda Martell Story.”

Martell was the first Black woman to perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville at the height of the CIvil Rights movement in 1969. The upcoming documentary tells the story of her being the most commercially successful Black women artist in country music.

Following the trailer, the 2004 Country Music Television (CMT) documentary “Waiting in the Wings: African-Americans in Country Music” played. In this film, country music legends from the producing, the singing, and the promotional side came together with scholars to share about the influence of Black people on the typically whitewashed genre.

The documentary did more than just mention the past, but also showcased five young Black artists including American Idol finalist Kimberly Locke, Crub recording artists Trini Triggs, Vicki Vann, Star Search finalist Rissi Palmer and teenage siblings Buddy & Tina Wright.

After the 90-minute documentary, Wilborn hosted a brief interview with Marquia Thompson, the director of “Bad Case of The Country Blue.”

To Thompson, Martell is no new story. As the granddaughter of the singer, she discovered her story as she got older.

“I just always admired her for it,” Thompson said. “I’ve always kind of looked at her as if she was a super star.”

The fascination of her grandmother having an album just grew as she got older, beginning to grasp what Martell really did.

The film just wrapped and everything is in post now, with the goal of being finished and distributed in the fall, she said.

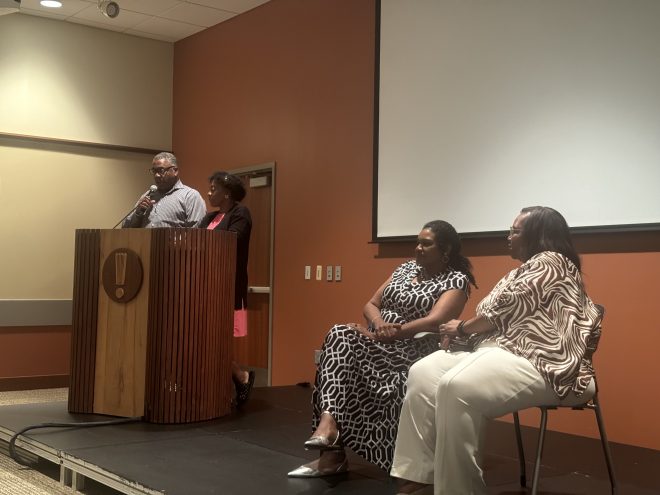

With the Zoom interview wrapping up, Jaclyn House, host of Good Day NWA, then invited the co-creators of “Waiting in the Wings,” Karla Winfrey and Herni Giles, to the stage for a Talkback & Q&A.

The production of the film was compacted into only about five months, but the concept of documentary Black country music had been on the minds of the two for a while.

“Finding the people, we knew who we wanted to talk to. We had access to them,” Giles said. “This was a great project for CMT, and being Country Music Television you would think that they would have done something like this beforehand, but they hadn’t.”

Winfrey described the process as a “labor of love” with the work that the two had put into the final product.

“Being that we had backgrounds as journalists, we were really going to dig deep, and really tell the truth,” she said, “because (there were) people in there that we actually knew.”

Winfrey knew the family of DeFord Bailey, growing up with them in church. From pointing out in the documentary that the influential artist was not even recognized in the Country Music Hall of Fame at the time of filming shed light on just one of the many injustices Black people face in the genre.

“I have to say I believe Henri, because it was the next year after we kind of embarrassed the industry…they put him in the hall of fame the next year,” Winfrey said.

The induction of Bailey into the Country Music Hall of Fame is the only fact in the film over the past two decades that needs to be updated, Giles said.

Another change is Rissi Palmer is now a recording artist without a label, supporting other country music artists, Winfrey said.

Similarly, Giles and Winfrey were only finally able to create their documentary with the support of someone they knew on the inside of CMT.

“Eventually, there were some arrangements that were about to occur at CMT,” Giles said, “and so we were trying to get this greenlit before some of those changes were made.”

A lot of politics were on the inside that affected these decisions and even 20 years later not a lot has changed, she said.

With more Black representation in the industry, specifically within the country music genre, networks and labels are still the gatekeepers.

“People who we interviewed, some of the things that they said was like ‘wow they really said that part out loud,’” Giles said. “Evelyn Shriver who was a long time mover and shaker on music road where she said ‘unless they change their skin color they are not going to be accepted’ and that’s pretty much the truth even now we see a lot of talent, but it’s the acceptance isn’t there.”

The two commented on the desire to create an updated documentary, including more information that couldn’t make it into the sold out CMT 2004 production.

“We had a lot more than what you saw. A lot had to be cut,” Giles said.

Winfrey added to that, saying that the documentary was done and they had to keep cutting because everybody wanted in.

“We had to call the big big boss of the whole MTV, CMT, the whole thing. We had to call her and tell her some stuff that was going on that next day she flew somebody in,” Winfrey said, “She flew the next day and said ‘what you all had on that paper you had, that’s what I need to see.’”

They made the decisions to sacrifice parts of the first one for the culture in order to get it made, she said. Although nothing is official, the plan is to own the follow up documentary.

To close the celebration of Black Music Month, a raffle of items from artists featured in the documentary, including Rissi Palmer, Cavender’s gift cards and other country related goodies were given out to the audience.

Comments